Why we jump to solutions (and why that doesn’t work)

It’s a familiar pattern: a team spots a problem or opportunity, proposes a promising idea, and quickly rallies around it. Pretty soon, a feature list is being built. All before developing a shared understanding of the problem they’re helping solve.

The leap happens for familiar reasons: we’re wired to fix things, leaders want action, and teams assume they understand the problem because they are deep in the weeds every day. But this kind of rapid-fire solutioning comes with real costs.

Organizations can invest months of time and budget into work that doesn’t meet customer needs or move the business forward. They may build something that technically works but leaves the underlying problem unclear and unaddressed.

In the end, a process that looked efficient resulted in a solution that must be reworked or decommissioned rather than celebrated and built upon.

Making more room for questions with a balanced approach

The reality is that not all opportunities come from the people who use our products and services. Even if we strive for a people-first approach, sometimes, business problems or technological realities must take our focus.

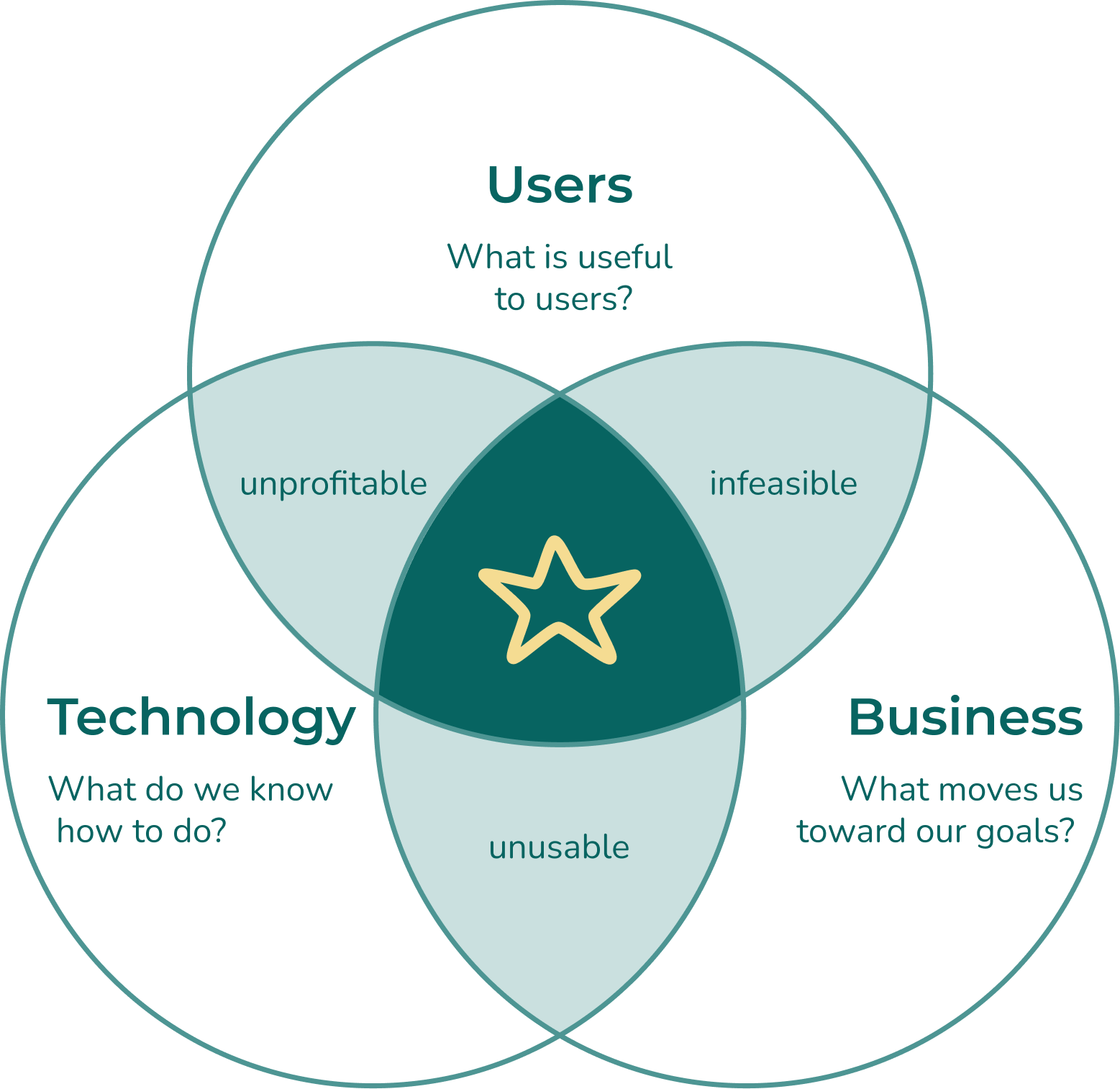

That means considering an idea through three distinct lenses:

- Users: What is useful to users?

- Business: What moves us toward our goals?

- Technology: What do we know how to do?

When any of these perspectives is missing, teams risk building something undesirable, unusable, unprofitable, or infeasible. When considering a new idea, consider which of these perspectives it’s primarily coming from and consider how it could impact the other two.

Getting from the first idea to the right idea

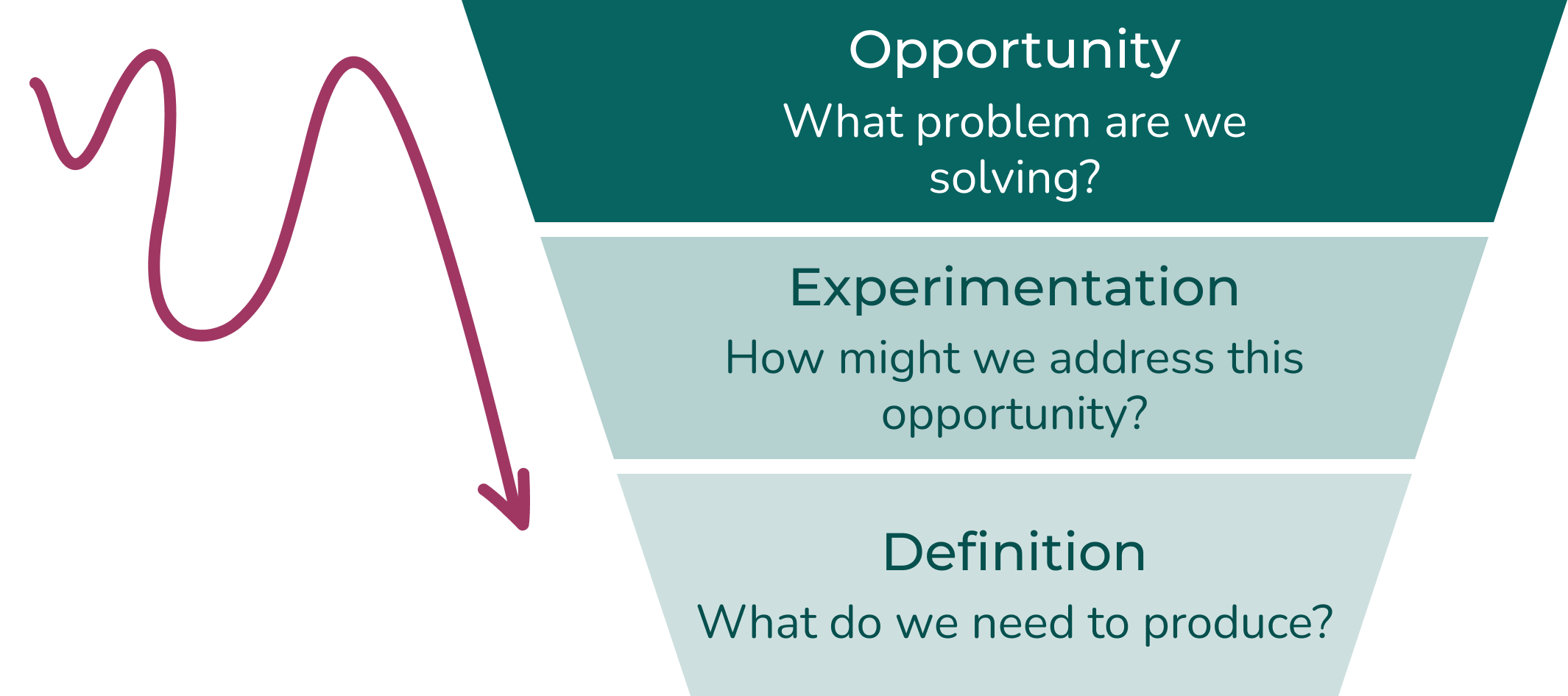

Once teams consider the problem from all three angles, they still need a path that keeps them from slipping back into solution-first thinking. That’s where a simple three-stage progression helps channel efforts towards the right idea, not just the first idea.

1. Opportunity: Understand the core problem

By starting with “What problem are we solving and for whom?”, we shift from chasing ideas to investigating the opportunity. Framing it as a problem to solve will help root the opportunity in a real need.

2. Experimentation: Learn quickly

Experimentation is often skipped due to perceived cost and delays, but experimenting with ideas does not require extensive development or even an MVP.

Instead, start with a set of questions or assumptions that experimentation could help answer. For example:

- Users: What are they trying to accomplish? What needs to be true for this to have an impact? Is this a critical need?

- Business: What’s the potential ROI? What’s the addressable market? Who is responsible for this internally?

- Technology: What technology stack might best enable this? What can we utilize that we already have?

From there, develop a simple experiment that could answer each question or validate each assumption – the shortest possible path to getting an answer with reasonable confidence. No minimum viable products (MVPs) or fully developed products. Think static screens, storyboards, advertisements, or simple sketches. Give your participants something to react to, not just words or a blank page.

This is a minimum testable concept, not the final product. Don’t test what you think the right thing is – test what you think will give you the clearest, fastest answer.

3. Definition: Document priorities and share findings

After running a series of small experiments, patterns are likely to emerge. Now’s the time to create a hypothesis and MVP that can be measured and adjusted.

Finally, don’t keep your findings to yourself. Implementation teams that have direct visibility into evolving business, technology, and user needs can make better informed micro-decisions, which leads to more intuitive user interactions and space for platform growth.

By sharing our findings with end users, we show a growing awareness of their needs and help develop a dialog that will naturally balance innovation with real-world constraints.

Why it matters

The first idea is rarely the right one. But with curiosity, small experiments, and a willingness to be wrong early, teams find the right idea faster, solutions address real problems, and innovation becomes intentional.

Don’t let a single idea get in the way of innovation. Experiment before devising a solution and validate assumptions.

- Clearly articulate the problem your team is solving before coming up with a solution.

- Test what you think will give you the clearest, fastest answer, not what you plan on building.

- Create a hypothesis and MVP that can be measured, adjusted, and shared beyond the core innovation team.

So next time you feel yourself rushing toward a solution, pause and ask: What do we need to know first?